Pros and Cons of Letting NCAA Student-Athletes Profit From Their Likenesses

Other Sports | February 13, 2021

There’s a crucial point that could be overlooked in the debate over NCAA athletes’ new avenues for making money. It reminds Hidden Take of an old philosophy maxim, “all infants’ mothers are women, but not all women are infants’ mothers.”

A majority of fans are fine with students making money from their likenesses while suited-up for a program. Advertising dollars are watched more closely than FBS or NCAAB recruiters are, highlighted by the belief that while schools don’t “purchase” players any more, the top dogs in Division 1 continue to flirt with corruption when gobbling-up 5-stars for the next freshman class. Advertisers can’t afford to defraud the establishment quite so often, since their business is in the public’s eye by definition. Even a Super Bowl ad considered to be in bad taste can cost a company dearly in public relations.

The Jeep ad is not just tone deaf, but it doesn't even reflect the image of America today in diversity, in inclusion, or even fundamentally.

– an old church

– a cowboy

– riding off into the sunset on a "jeep"Not it guys… definitely not it.

— Kennyatta (@ItsKennyatta) February 8, 2021

Struggling kids getting a lifeline from Campbell’s soup ads is among the most innocuous and beneficial things one can imagine, a transfer of wealth from “old money” to a pool of young people, including many POC from poor communities, who can use it to build a financial foundation in case a lucrative pro contract in their sport turns into a pipe dream.

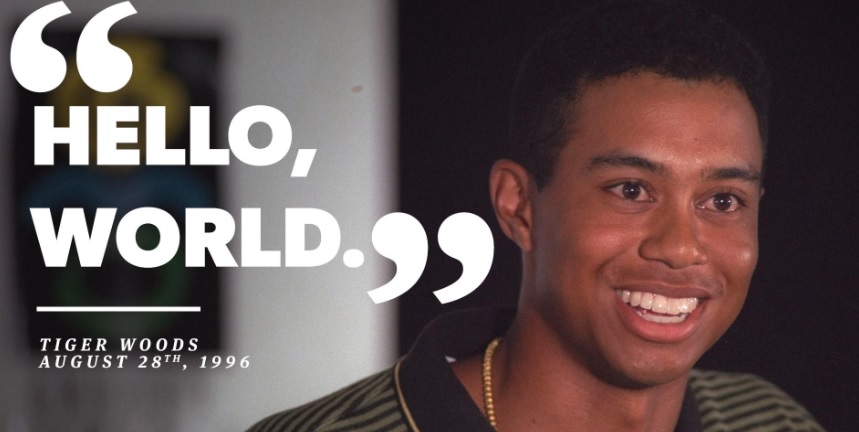

Bobby Jones, the greatest amateur golfer of all time, parlayed his USGA notoriety into millions. Tiger Woods began building a business empire long before he turned “pro” on the PGA Tour.

If golf, the stuffiest sport on the planet, can allow its amateurs to profit from success in competition, then the NCAA can.

But there’s also a tightrope to walk. NCAA programs must be beholden to advertisers. Advertisers must not be beholden to programs.

Imagine if SEC, ACC, and Big Ten powerhouses are allowed to build consortiums, or “portfolios” of advertisers, each loyal to a single mascot. As in the political world, sports media would be co-opted by an “oligarchy” of powerful boosters and commercial interests that preferred squeaky-clean “news” coverage of student-athletes and coaches.

Rival schools and low-budget upstarts could be hit with smear stories paid-for by proxy with big-shot teams washing the money through its friends. Think of how star QBs preparing to play Alabama somehow always become the focus of controversy until after ‘Bama wins, and try to conceive of such nasty business on a national scale 24/7.

Statement from FSU AD Stan Wilcox on Jameis Winston autograph controversy… pic.twitter.com/Gg0oLcT6oU

— 💫🅰️♈️🆔 (@ADavidHaleJoint) October 17, 2014

Jocky McRaider, the 5-star recruit out of Skyline HS in Texas, would be sweet-as-ether to his “old” commitment on Twitter with days to go before the FBS season-kickoff: “After careful consideration, I’ve decided to forego my commitment to Sun Belt U. and sign with Nabisco, I mean, the Kentucky Wildcats.”

The above nightmare can be averted by making sure programs have to compete to maintain client-relationships, just like a Madison Avenue ad agency. Contracts with collegiate sports programs that attempt to facilitate corporation-like collusion should be prohibited, as should any player-advertising campaigns funded by media CEOs and donors.

It’s nice that social media can spark an uprising based on a single lonely tweet or Instagram post in which one person notices something. The public comes down hard on advertisers (and sports programs) who misbehave, making the prospect of student-athletes from Tuscaloosa to Rhode Island profiting from their likenesses a harmless one if transactions are above board and reporters’ voices are independent.

Close regulation of NCAA player-advertising will protect the very same kids whom the practice can help the most.